Translate this page into:

Uncommon synovial pathologies

Corresponding author: Ankur Patel, Assistant Professor, Department of Radiodiagnosis, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Bhopal, India. ankur.radiodiagnosis@aiimsbhopal.edu.in

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Kumar A, Patel A, Sarawagi R, Malik R, Rahman NU, Balaji N. Uncommon synovial pathologies. Future Health. 2024;2:44–51. doi: 10.25259/FH_16_2024

Abstract

The synovium is a specialized tissue lining the synovial joints, bursae, and tendon sheaths of the body. It is affected by various localized and systemic disorders. Synovial diseases can be broadly classified as inflammatory, infectious, degenerative, proliferative, hemorrhagic, and neoplastic. Injuries to other structures within the joint, such as cartilage, may also be caused by pathological processes that affect the synovium. Early detection of synovial diseases is critical to avoid irreversible joint damage. Understanding the typical imaging features of synovial diseases can help in accurate diagnosis and prompt treatment. Therefore, imaging plays a crucial role in detecting synovial diseases at an early stage. This pictorial review highlights the unusual synovial pathologies, such as synovial chondromatosis, pigmented villonodular synovitis (PVNS), giant cell tumor of tendon sheath (GCTT), hemophilic arthropathy, lipoma arborescens, and synovial sarcoma.

Keywords

Synovium

Synovial chondromatosis

Pigmented Villonodular Synovitis

Giant cell tumor

Giant cell tumor of tendon sheath

Hemophilic arthropathy

Hemophilia

Lipoma arborescens

Synovial sarcoma

INTRODUCTION

Synovial joints exhibit a bipartite architecture characterized by an external fibrous capsule and a delicate internal synovial membrane, the “Synovium.” The fibrous capsule, composed of dense connective tissues, provides structural stability and encloses the joint cavity.

The synovium, a specialized membranous lining of mesenchymal origin, invests the diarthrodial joint surfaces, bursae, tendon sheaths, intra-articular ligaments, and periosteal surfaces devoid of hyaline cartilage.1 Notably, it excludes certain intra-articular structures such as articular cartilage, menisci, labra, and bare areas.2

The synovial membrane in joints has two layers, synovial intima and subsynovium. The intima contains synoviocytes that produce hyaluronic acid for the synovial fluid, whereas the subsynovium contains vascular and lymphatic networks for joint clearance. This membrane helps protect the joint from wear and tear by providing lubrication, shock absorption, and a filter system, maintaining optimal joint function.3

The synovial membrane can develop various neoplastic and non-neoplastic or inflammatory processes that can affect a single joint or multiple joints. Early detection of synovial diseases is important to prevent irreversible joint damage, for which one or more imaging modalities may be employed.

Plain radiography, ultrasonography (US), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are utilized in the diagnosis and follow-up of synovial diseases.

Early stages of joint diseases show mild synovial thickening and joint effusion, making plain radiographs appear normal. However, in advanced stages, they can be useful to identify joint destruction and secondary degenerative changes. They can also evaluate other features such as ossification or calcification of intra-articular bodies, joint alignment, and bone density.

Ultrasound is an excellent first-line modality, especially for small and superficial joints. It readily detects the synovial thickening, vascularity, joint effusion, and bony destruction before these changes are apparent on the radiographs. It also serves as a guide for image-guided sampling and other interventions relevant to these pathologies.

MRI, because of its high soft-tissue contrast resolution, is the current gold standard imaging modality. Normal synovium is indistinguishable from joint fluid on fat-saturated, T2-weighted, and Short tau inversion recovery (STIR) images, becoming evident only after intravenous (IV) contrast administration. It is less than 2 mm thick and demonstrates smooth and uniform contrast enhancement.4 Apart from the synovium, other associated structures, such as articular cartilage, subchondral bone, ligaments, muscles, and juxta-articular soft tissues, can be evaluated. Intravenous and intra-articular contrast may also be employed in select cases to enhance the diagnostic information.

CT scan has a limited role and is predominantly used to look for bony details where the plain radiographs are inadequate or in cases of involvement of complex joints such as sacro-iliac joint.5

The most commonly encountered synovial pathologies are inflammatory and infectious diseases of the synovium with other associated changes.

In this pictorial essay, we discuss the unusual synovial pathologies, including synovial chondromatosis, pigmented villonodular synovitis (PVNS), giant cell tumor of tendon sheath (GCTT), hemophilic arthropathy, lipoma arborescens, and synovial sarcoma.

SYNOVIAL CHONDROMATOSIS

Synovial chondromatosis, also known as synovial osteochondromatosis, is a benign synovial proliferative monoarticular disorder with hyaline cartilage nodules that enlarge and detach from the synovium over time. The knee, followed by the hip, is the most commonly involved site6, and it has a predilection for adult males.

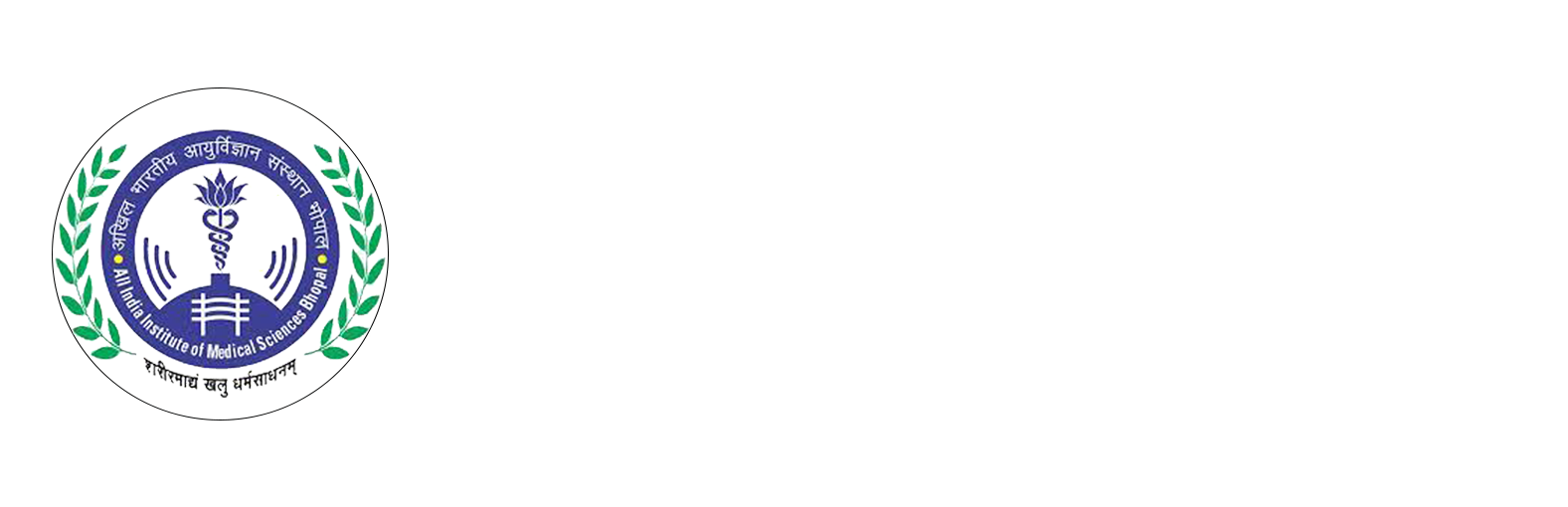

Primary synovial chondromatosis is a benign disorder that affects one joint, characterized by the growth of multiple cartilaginous loose bodies within the joint [Figure 1]. The condition is caused by abnormal chondroid nodule growth in the synovium.

- (a) A 37-year-old male with complaints of left-sided shoulder pain for two years. Frontal radiograph of the left shoulder shows multiple ossified loose bodies, some of them showing ring and arc-type of calcifications, characteristic of synovial chondromatosis. (b) Axial T2 image shows multiple oval-shaped bodies showing a targetoid appearance with an intermediate signal in the center and a hypointense signal at the periphery. (c) Sagittal T1 image shows multiple intra-articular bodies, showing intermediate to hypointense signal. (d) Axial Multiple echo recombined gradient echo MERGE (GRE) sequence shows mild blooming or susceptibility artifacts in the intra-articular bodies.

The imaging findings on radiography can vary depending on the stage of the disease and the extent of calcification or ossification of the cartilaginous nodules. These nodules are typically uniform in size and usually are multiple in number.

The unmineralized nodules can be inconspicuous on radiographs, but on MRI, they demonstrate typical chondroid-type signal characteristics, appearing intermediate to low signal on T1 and high signal on T2WI. Blooming artifacts are seen on gradient images. In cases where all the nodules are fully ossified, a low signal is seen on both T1- and T2-weighted images.7

In the secondary type (related to degenerative, neuropathic arthropathy, and trauma), there are additional intra-articular loose bodies that are large, vary widely in size, and frequently ossify, in contrast to the smaller and more uniformly sized intra-articular bodies seen in the primary type.8

PIGMENTED VILLONODULAR SYNOVITIS

Pigmented villonodular synovitis (PVNS) is a benign synovial disease of uncertain etiology. It usually affects a single joint, with the knee being the most commonly affected joint.

It is more commonly seen in patients in their third and fourth decades. Initially, patients present with a painless swelling that may appear similar to a joint effusion. Over time, pain develops along with limited joint movement and hemorrhagic joint effusions.

Plain radiographs of the affected joint may appear normal or may show intra- and peri-articular soft tissue. Bone density and joint space are usually well preserved, but bone erosions may be present.

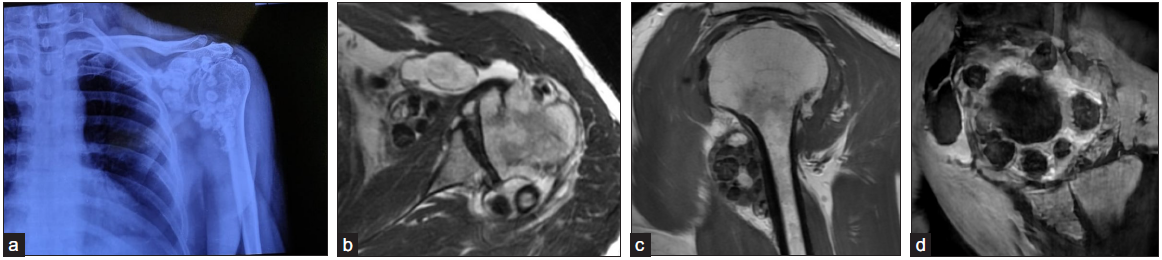

On MRI, PVNS is identified by multiple, lobulated, synovial-based intra-articular soft tissue masses [Figure 2]. These lesions generally have intermediate to low signal intensity on both T1- and T2-weighted images. PVNS lesions tend to bleed, which results in the deposition of very low signal intensity hemosiderin that shows blooming on GRE sequences, and this serves as a key feature to differentiate it from in-mineralized deposits of synovial chondromatosis. Erosion into the adjacent bone or soft-tissue structures is seen in later stages and is well demonstrated by MRI.9

- (a-b) A 26-year-old male presented with right knee pain and swelling for one year. T2FS axial and sagittal images and (c) T1 coronal image show moderate joint effusion, and synovial proliferation with multiple synovial based nodular deposits. These deposits show central, intermediate, and peripheral hypointense signals on both T1 and T2. (d) On gradient Multiple echo recombined gradient echo MERGE sequence, they are showing blooming at the periphery, which is characteristic of pigmented villonodular synovitis (PVNS). The synovial deposits did not show any evidence of mineralization on radiographs (not shown).

PVNS can be diffuse or localized. The latter is known as localized nodular synovitis and commonly occurs in the infrapatellar fat pad. Lesions in this form are smaller and better defined than those in diffuse PVNS, resulting in less restriction of joint motion.

GIANT CELL TUMOR OF TENDON SHEATH

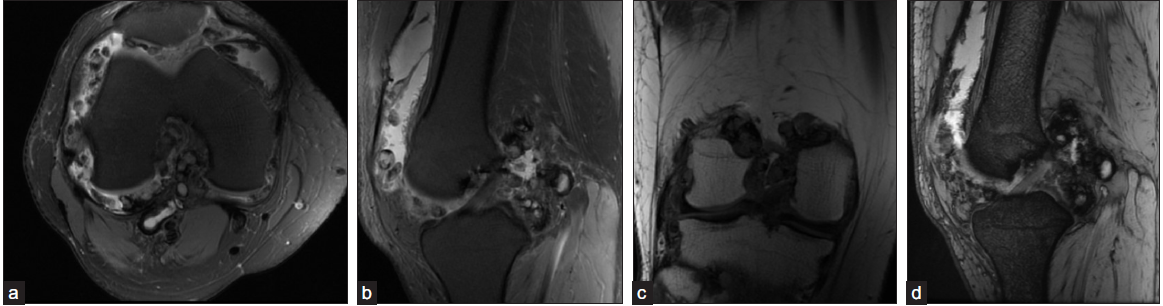

Giant cell tumors of the tendon sheath (GCTT) are benign lesions that occur in the synovium. They are the second most common soft tissue tumor of the hand and cause painless swelling. There are two subtypes: localized and diffuse. Localized GCTT mainly affects the hand and wrist, whereas the diffuse type tends to affect the large joints more commonly. Patients usually present with slow-growing painless swelling.

Radiographs reveal a well-defined soft tissue mass that may cause smooth scalloping of adjacent bones. Ultrasonography (USG) shows a well-defined, hypoechoic lesion that appears either homogeneous or heterogeneous. This lesion may or may not have internal vascularity, but the vascularity is only mild if present. MRI shows a well-defined tumor in relation to the adjacent tendon. The lesion contains hemosiderin pigments that cause a low signal intensity on T1WI and T2WI [Figure 3]. Bony erosions can also be seen on MRI. On gradient images, blooming artifacts can be seen because of the hemosiderin content. The lesions show enhancement on postcontrast scan. MRI also shows the relationship of the tumor with soft tissues and joint space.10

- A 27-year-old male complains of painless swelling at the ulnar aspect of the third digit of his right hand. (a-b) (ultrasound images) show a well-defined heterogeneous hypoechoic lesion with mild internal vascularity. (c) (coronal T1WI) shows a well-defined intermediate signal lesion involving the palmar and ulnar aspects of the right third digit. On the Axial T2W image (d), the lesion shows hypointense to intermediate signal and appears adherent to the adjacent flexor tendon sheath. The coronal 3D MERGE sequence (e) demonstrates smooth scalloping of the adjacent phalanx caused by the lesion (arrow). (f) Postcontrast coronal image shows moderate heterogeneous enhancement. Ultrasound guided fine needle aspiration cytology was done, which suggested the diagnosis of a Giant cell tumor of tendon sheath (GCTT).

The differential diagnosis of GCTT include ganglion cyst, hemangioma, peripheral nerve sheath tumor, synovial sarcoma, and fibromatosis. Although GCTTs are considered to be benign lesions, the recurrence rate is high after local excision.

HEMOPHILIC ARTHROPATHY

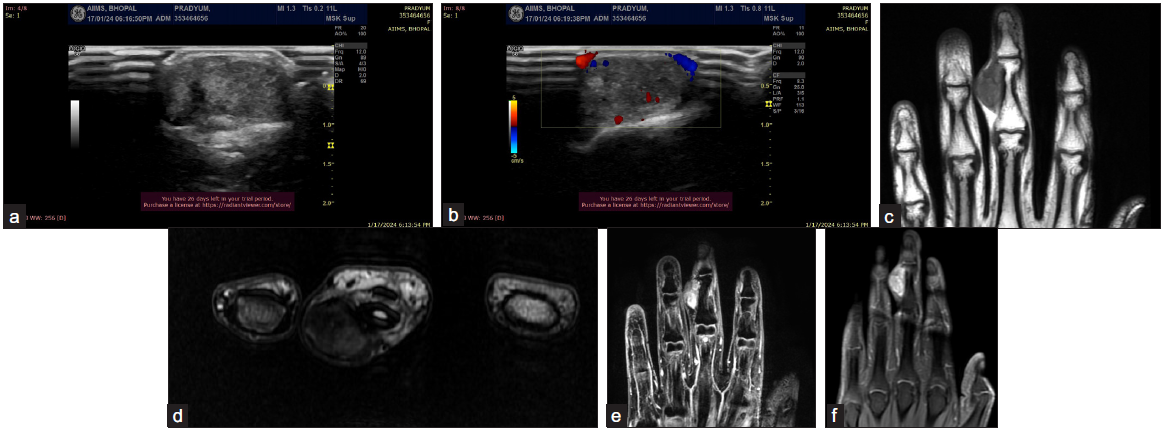

Hemophilic arthropathy is a joint disease that occurs in patients with hemophilia due to repeated episodes of intra-articular bleeding. Hemophilia is an X-linked recessive disorder that affects 1 in 10,000 males.5 Hemophilic arthropathy predominantly affects large joints, with the knee joint being the most commonly involved.11

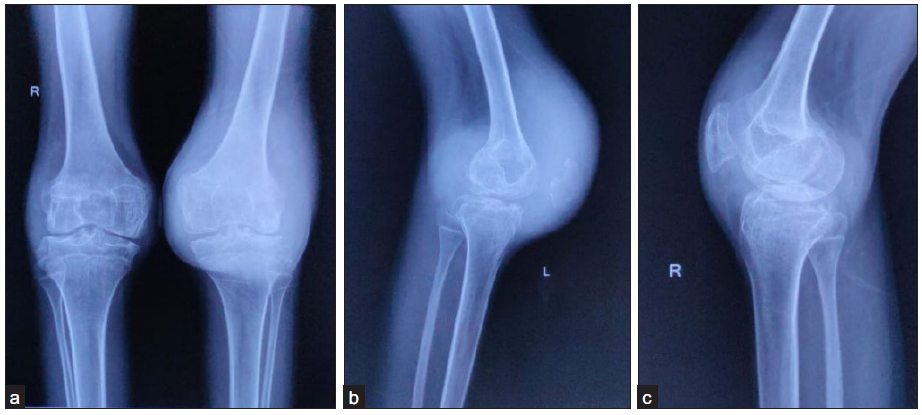

Radiographs are helpful in demonstrating the classical bony changes seen in the late stages of the disease, such as osteopenia, epiphyseal overgrowth, large erosions, squaring of the patella, widening of the intercondylar notch, subchondral cysts, and joint space narrowing [Figure 4].

- The frontal and lateral radiographs of both knees of a 16-year-old male with complaints of recurrent bilateral knee joint swelling. Factor VIII levels were found to be at 25% (normal range 50%–150%). (a-b) Frontal and lateral radiographs of the left knee, show large soft tissue density (due to joint effusion) with widening of intercondylar notch, mildly reduced joint space, and few small bony erosions at the tibial plateau and posterior surface of patella. (a-c) Frontal and lateral radiographs of the right knee show widened intercondylar notch and periarticular osteopenia. The soft tissue density is less remarkable as compared to the left knee.

The severity of the disease can be assessed by a radiograph-based staging system [Table 1].12

| Stage I: | Soft tissue swelling (± joint effusion) with normal joint surfaces |

|---|---|

| Stage II: | Stage I + periarticular osteoporosis and epiphyseal overgrowth |

| Stage III: | Erosions, sclerosis, and subchondral cysts. The joint space is preserved. |

| Stage IV: | Stage III + focal or diffuse joint space narrowing |

| Stage V: | A stiff contracted joint with significant degenerative changes |

Ultrasound can easily detect joint effusions and synovitis, but it cannot recognize cartilage damage. Also, hemarthrosis may exhibit varying echogenicities depending on the age and number of bleeding episodes.

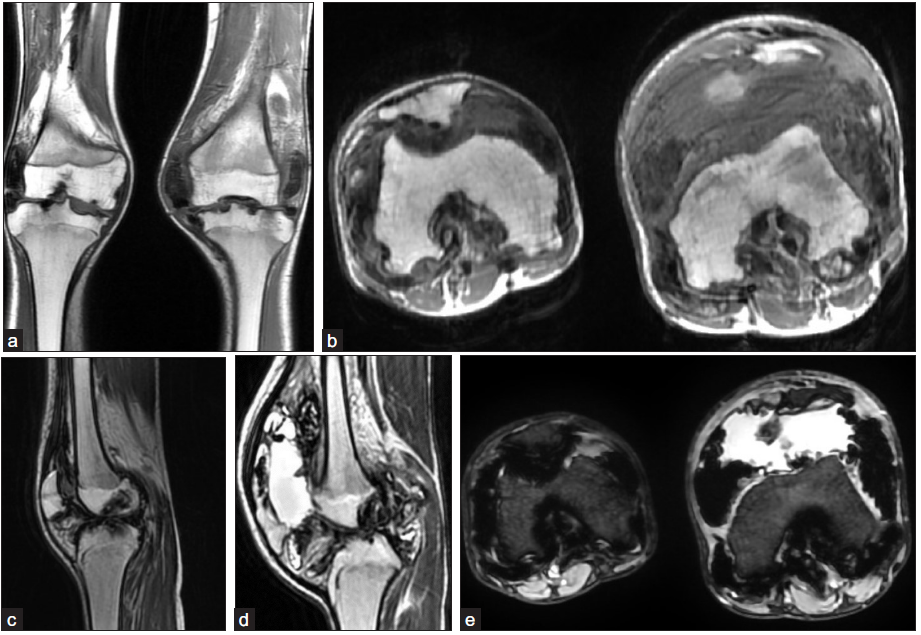

MRI shows thickened synovium, which shows uniform low signal intensity on T1WI and T2WI with blooming on gradient sequences due to blood products within [Figure 5]. On postcontrast scans, the synovium shows enhancement due to associated synovial inflammation. Other features such as joint effusion, cartilage loss, erosions, and joint destruction are also very well seen on MRI.5

- A 16-year-old male with complaints of recurrent bilateral knee joint swelling and decreased levels of Factor VIII. (a-b) Coronal and axial images of bilateral knee show areas of synovial proliferation causing erosions into the articular surface of adjacent bones. (c-d) Sagittal T2W images of the right and left knees show diffuse irregular, markedly hypointense thickening of the synovium, with distension of the suprapatellar recess of the left knee due to fluid. The fluid shows an intermediate signal on T1, indicating probable hemorrhagic composition. (e) On gradient sequences the thickened synovium shows marked blooming. Based on the clinical, radiographic, and MRI findings, a diagnosis of bilateral hemophilic arthropathy was made.

Important imaging differentials include juvenile idiopathic arthritis and synovial chondromatosis, which may show similar imaging findings, especially on radiographs. A clinicopathological diagnosis of hemophilia is crucial to the diagnosis of hemophilic arthropathy and essentially rules out the other conditions.

LIPOMA ARBORESCENS

Lipoma arborescens is a rare condition affecting synovial linings of the joints and bursae, with “frond-like” depositions of fatty tissue. The knee is the most commonly affected joint (particularly the suprapatellar bursa).

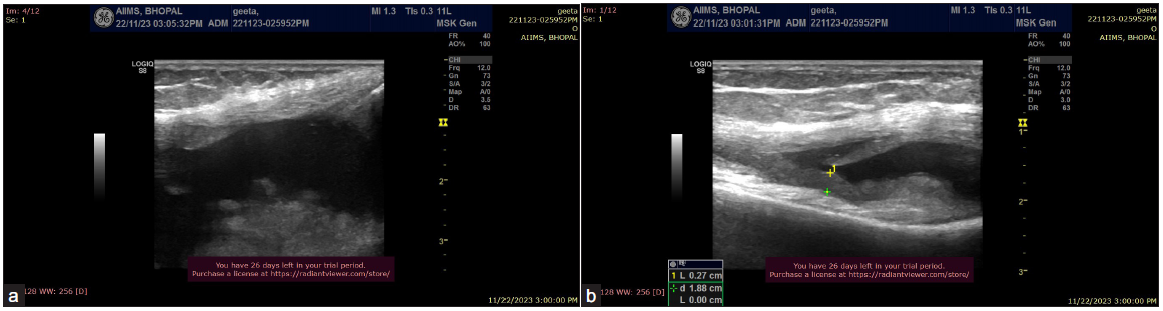

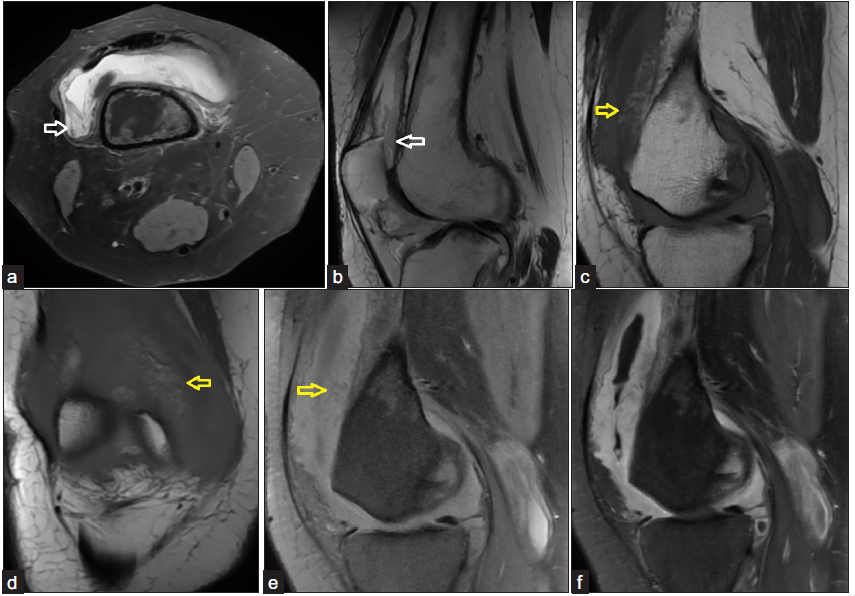

Radiography is generally nonspecific in most cases but may show fatty lucencies. MRI is the modality of choice for diagnosis. A typical appearance is a fat-containing frond-like area outlined by concurrent joint effusion [Figure 6]. The lesion follows the signal intensity of fat (high signal on T1WI and T2WI) on all sequences that tend to suppress on fat-suppressed sequences [Figure 7].13

- A 48-year-old female presented with right knee pain and swelling for one year. (a-b) Ultrasound demonstrates moderate joint effusion with echogenic frond-like thickening of synovium projecting into the joint effusion.

- A 48-year-old female presented with right knee pain and swelling for one year. (a-b) Axial T2FS and sagittal T2 images show moderate joint effusion with synovial thickening (white arrow). (c-d) Sagittal and coronal T1 images show areas of hyperintense signal within the thickened synovium (yellow arrow), (e, yellow arrow) which showed complete loss of signal on fat-saturated T1 sequence. (f) Postcontrast T1FS sagittal scan showing homogeneous enhancement of the thickened synovium. The findings of synovial proliferation with areas of fat signal intensity within are characteristic of lipoma arborescens.

SYNOVIAL SARCOMA

Synovial sarcoma is the third most common soft-tissue sarcoma in adults. Men and women are affected equally. Most synovial sarcomas occur in the extremities, commonly the lower extremities.

Patients usually present with a slowly growing, sometimes painful mass that can be felt. Due to the gradual onset of symptoms, there may be a delay in diagnosis. In most cases, the tumors are larger than 5 cm at the time of diagnosis. However, superficial tumors can be detected when they are smaller in size and have smooth contours with a homogenous architecture, which can mimic benign lesions. Unfortunately, the local recurrence and distant metastasis rates are very high. A tumor size larger than 5 cm is considered a poor prognostic factor. These tumors may contain intratumoral calcification and necrosis. The most common location for these tumors is the lower extremities, specifically the popliteal fossa.14

On the radiographs, findings include a juxta-articular soft tissue mass that may contain calcifications. USG reveals a heterogeneous, predominantly hypoechoic mass showing vascularity on the color doppler. Areas of internal necrosis are often seen and more common in larger lesions.

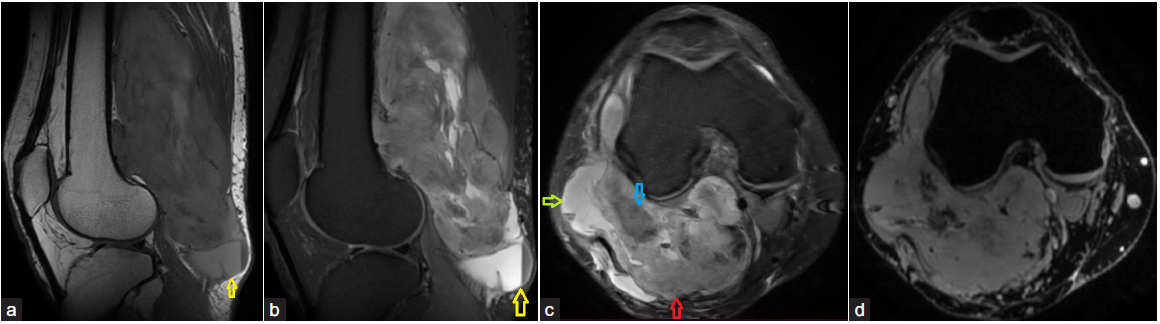

MRI is the modality of choice to stage the tumor locally. The mass is usually large and relatively well defined. The signal intensity is variable on both T1WI and T2WI [Figure 8]. They can show a markedly heterogeneous appearance on fluid-sensitive/T2W sequences, ranging from very high signal (areas of necrosis and cystic degeneration), intermediate–high signal (soft tissue component), and low signal (dystrophic calcifications and fibrotic bands). This is sometimes referred to as a “triple sign” due to the presence of three areas of distinct signal intensity within the same lesion.15 Due to the high tendency of lesions to bleed, there might be areas of fluid hemorrhagic levels. It shows heterogeneous enhancement on the postcontrast scan.15 Locoregional lymphadenopathy may also be seen.

- A 30-year-old male presented with swelling and pain in the popliteal fossa for two years. The swelling was initially pea-sized, which then progressed insidiously to the current size. (a yellow arrow and b) Sagittal T1 and PDFS sequences show a large, well-defined multilobulated solid mass in the popliteal fossa, which shows heterogeneous intermediate signal intensity on both T1 and PDW images. There is also a loculus showing a fluid hemorrhagic level within, seen at the inferior end of the lesion (yellow arrow), which represents intralesional hemorrhage. Few other similar fluid-hemorrhagic levels were also noted. (c-d) Axial T2FS and gradient image show three areas of contrasting signal intensities, with cystic or necrotic areas appearing hyperintense (green arrow), solid components appearing intermediate (red arrow), and areas of mineralization showing hypointense signal (blue arrow) with blooming, on gradient sequences. This is referred to as a “Triple Sign” due to the presence of three areas of distinct signal intensity within the same lesion. Histopathology showed mild to moderately pleomorphic, oval to spindle shaped cells positive for SS18 and SMA, and a diagnosis of monophasic synovial sarcoma was given.

CONCLUSION

Synovial diseases are one of the frequently encountered conditions, which can be primary or may be secondary due to other joint diseases or systemic disorders. Detailed clinical history along with a multimodality imaging approach is pivotal to the diagnosis and guiding of the management. Some of these diseases have overlapping clinical features and can only be diagnosed confidently based on typical imaging findings. It is prudent for a radiologist to be aware of the imaging findings of common and uncommon synovial diseases for early diagnosis and prompt management.

Ethical approval

Institutional Review Board approval is not required.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent is not required as patient’s identity is not disclosed or compromised.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

References

- MR findings of synovial disease in children and young adults: Part 1. Pediatr Radiol. 2011;41:495-511. quiz 545–6

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spectrum of synovial pathologies: a pictorial assay. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2012;41:30-42.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morphology and functional roles of synoviocytes in the joint. Arch Histol Cytol. 2000;63:17-31.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MR Imaging knee synovitis and synovial pathology. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2022;30:277-91.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basic radiological assessment of synovial diseases: a pictorial essay. Eur J Rheumatol. 2017;4:166.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- MRI Signal Intensity–based approach to synovial masses. RadioGraphics. 2023;43:e220081.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imaging of synovial chondromatosis with radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2007;27:1465-88.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A pictorial review of primary synovial osteochondromatosis. Eur Radiol. 2008;18:2662-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pigmented villonodular synovitis and giant cell tumors of the tendon sheath: radiologic and pathologic features. Am J Roentgenol. 1999;172:1087-91.

- [Google Scholar]

- Giant cell tumors of the tendon sheath: analysis of sonographic findings. Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183:337-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pathophysiology of hemophilic arthropathy and potential targets for therapy. Pharmacological research. 2017;115:192-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grainger & allison’s diagnostic radiology essentials: grainger & allison’s diagnostic radiology essentials e-book. Elsevier Health Sciences. 2018;1035

- [Google Scholar]

- MR imaging of lipoma arborescens and the associated lesions. Skeletal Radiol. 2003;32:504-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Synovial sarcoma: imaging features of common and uncommon primary sites, metastatic patterns, and treatment response. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;199:W208-15.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radiological features of synovial cell sarcoma. Br J Radiol. 2008;81:346-56.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]